The New Trade Map - China’s Export Pivot to the Global South. Friday’s Edition

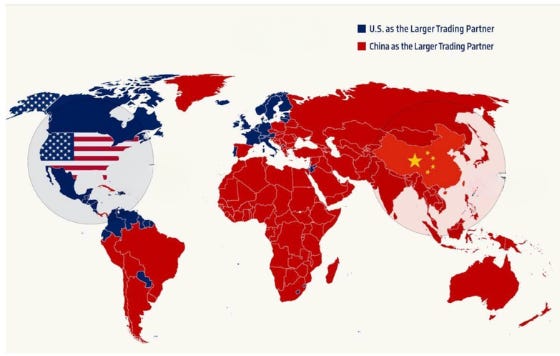

The trade map America isn’t on - Series 14 #5

The United States is not included in RCEP, the CPTPP, or EU-Mercosur, and while this is a significant disadvantage for American companies, something bigger looms. China is a member of only one, the RCEP, but trades heavily with members of all three trade blocs. The Trump-Republican administration has pushed all of these countries away from the U.S. and to China. Now, the United States faces a double disadvantage; it’s not a member of the trade blocs and Chinese goods are going to these countries and not to America.

In 2017, when Trump first took office, the United States received 18% of China’s exports. In May 2025, it was 7.1%, the lowest since 2001. China saw the tariffs Trump enacted in 2018 and understood what was happening: America would remain hostile regardless of who occupied the White House, and Biden kept the tariffs. Trump returned and raised them higher. China started building alternative trade partners.

China now exports $1.6 trillion annually to the Global South, 50% more than its combined exports to the United States and Western Europe ($1 trillion). These exports have doubled since 2015, with growth accelerating after each round of American tariffs. In the first three quarters of 2025, Chinese trade with ASEAN rose 9.6%, with Africa 19.5%, with Central Asia 16.7%, and with Latin America 3.9%.

ASEAN became China’s largest trading partner in 2020, displacing the United States, and by 2024 accounted for 16.2% of China’s total trade, up from 12.5% in 2017. Indonesia alone now imports $108 billion annually from China, triple the level of four years ago. Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand serve as manufacturing hubs where Chinese components get assembled into finished products, sometimes bound for Western markets that would tariff them if shipped directly from China.

Africa saw Chinese exports surge 25% in the first eight months of 2025, reaching $140.8 billion, while China extended zero-tariff treatment to goods from 53 (of 54) African nations. In the first half of 2025, African countries signed $30.5 billion in construction contracts with Chinese firms, five times more than the same period in 2024.

Latin America now accounts for 8% of Chinese exports. When Trump imposed his 145% tariffs in early 2025, Chinese manufacturers redirected shipments within weeks. Brazil, Colombia, and Chile welcomed the goods America refused to buy. President Xi hosted the leaders of all three countries in Beijing while tariff negotiations with Washington stalled. Trump’s tariffs are driving China’s growth.

This is long-term orientation: absorbing short-term losses while building market positions that compound over decades. A Chinese appliance manufacturer locked out of Walmart can sell to Indonesian and Nigerian consumers whose incomes are rising. In ten years, those markets will matter more than America does today. Trump’s tariffs hurt Chinese exporters in 2018. By 2025, those same exporters had customer bases that did not depend on American buyers.

Trompenaars calls the approach particularism: adapting terms to each partner rather than imposing uniform rules. China negotiates differently with Brazil than with Indonesia, offers infrastructure investment to some countries, tariff-free access to others, and technology partnerships to those seeking industrial upgrading.

In Hornby’s framework, China operates as West Sage and North Power-seeker combined. West is the Sage: methodical, building systematically on verified knowledge, adjusting strategy based on results. North is the Power-seeker, but here the drive for power results in building partnerships rather than dominanting. Where Trump’s North orientation demands submission and punishes defiance, China’s version offers alternatives. When Trump threatened 145% tariffs, Xi welcomed Latin American presidents to Beijing. When Trump demanded that Europe let America buy Greenland, Xi met with Macron and other European leaders to strengthen ties.

What does this mean for the future? S&P analysts put it bluntly: “The result could be a new order of global commerce where South-South trade becomes the new center of gravity, and Chinese multinationals emerge as the new key players.” America remains in this order, but no longer the leader.

Tomorrow: What these shifts mean for America’s position in the global economy.

If you enjoyed this article, buy me a coffee!

Brilliant analysis of how tariffs can bacfire strategically. The data on China's $1.6 trillion pivot to the Global South really underscores something: once supply chains adapt, they dont just revert back. I saw this firsthand when a client's manufacturing partner diversified after 2018 and never came back to the U.S. market even when it made sense financially.