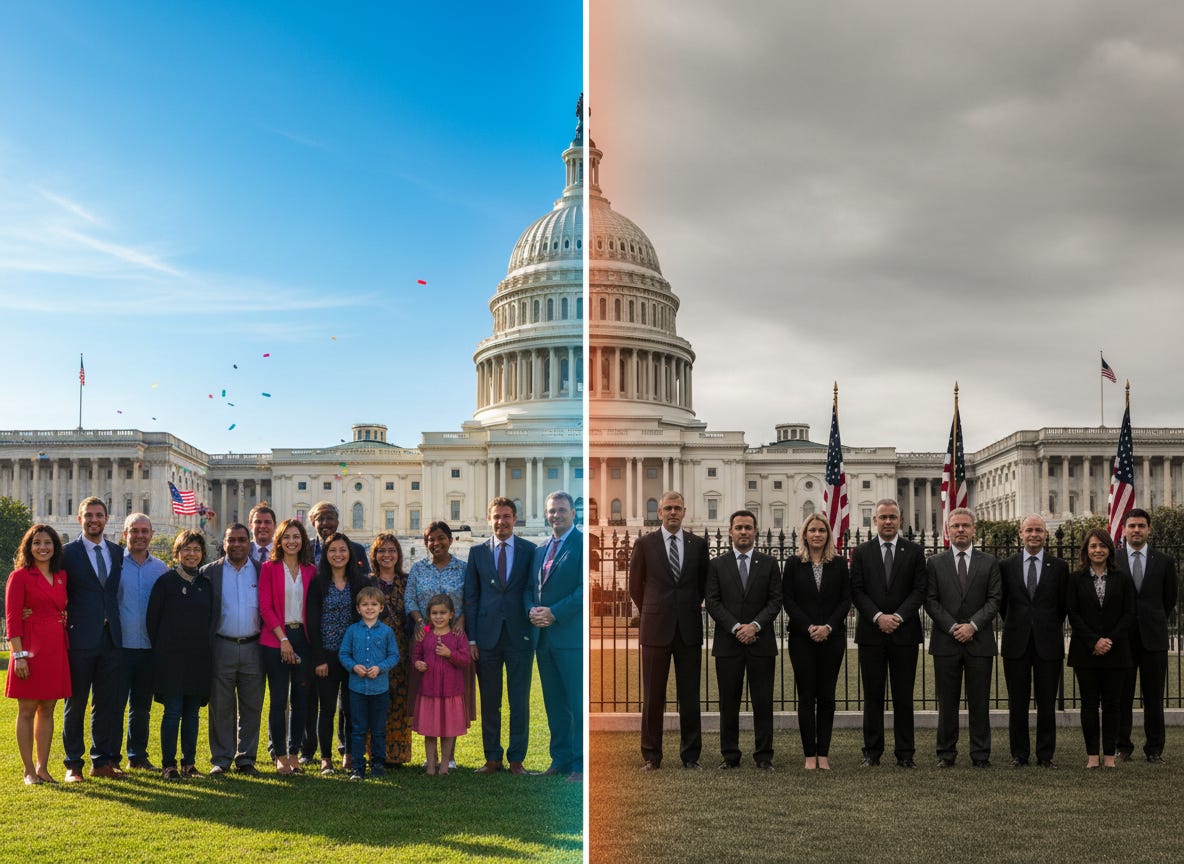

WHO GETS TO BE ONE OF US? CIVIC NATIONALISM AND ETHNIC NATIONALISM. MONDAY'S EDITION

Civic nationalism or ethnic nationalism - Series 13 #1

On January 19, 1989, Ronald Reagan delivered his final address as president. He quoted a letter: You can live in France but never become French. You can live in Japan but never become Japanese. But anyone can become American. Reagan used this idea to define the United States. In his view, being an American was about a commitment to a set of rules and id…