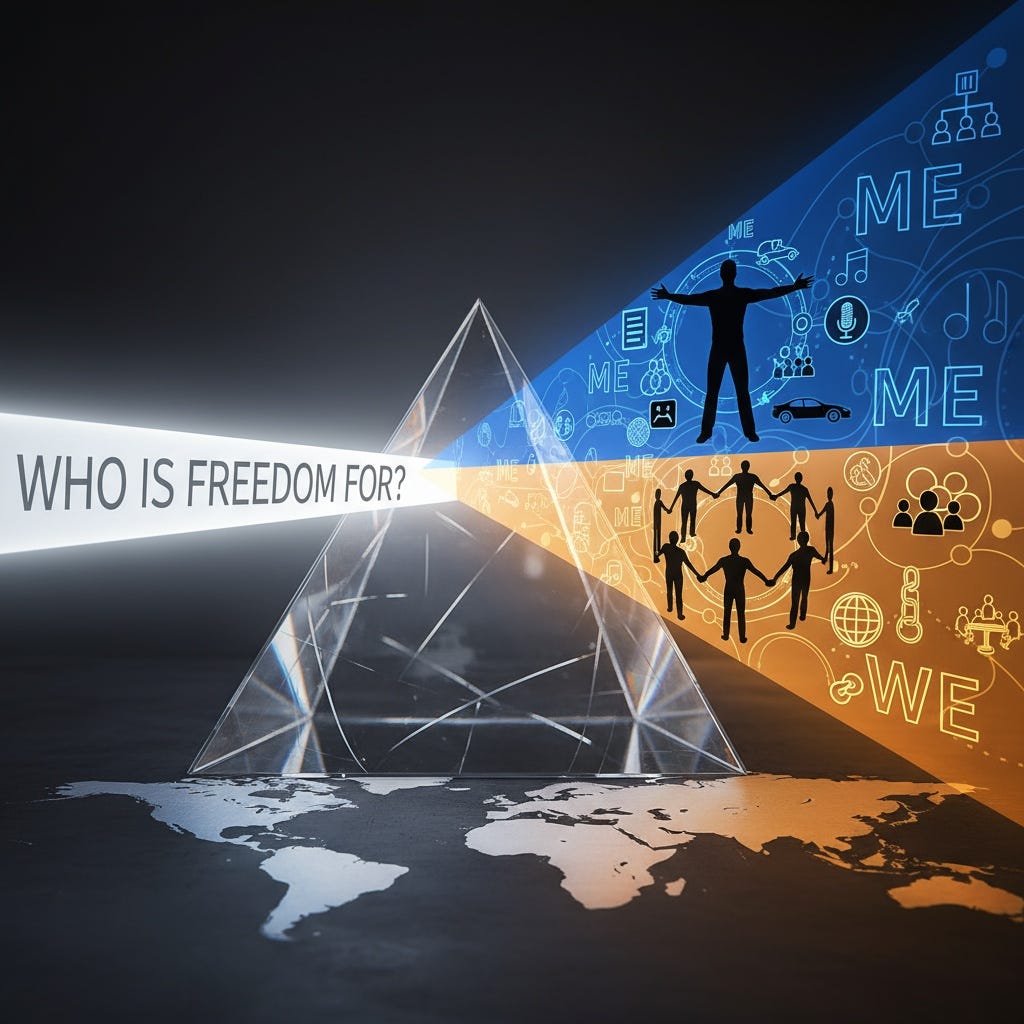

Tuesday Edition — Who Is Freedom For?Individualism vs. Collectivism

Freedom Isn’t What You Think It Is — A Cultural Analysis

Who is freedom for?

This is a nonsense question for Americans and many Westerners because freedom is always about “me.” Freedom is doing what “I” want. It is pursuing “my” desires, “my” goals, and “my” wants. Who else is freedom for if not “me?”

In individualistic cultures, freedom is designed for the individual, for the person acting. But, in collectivis…