There Is No Best System: Monday Edition

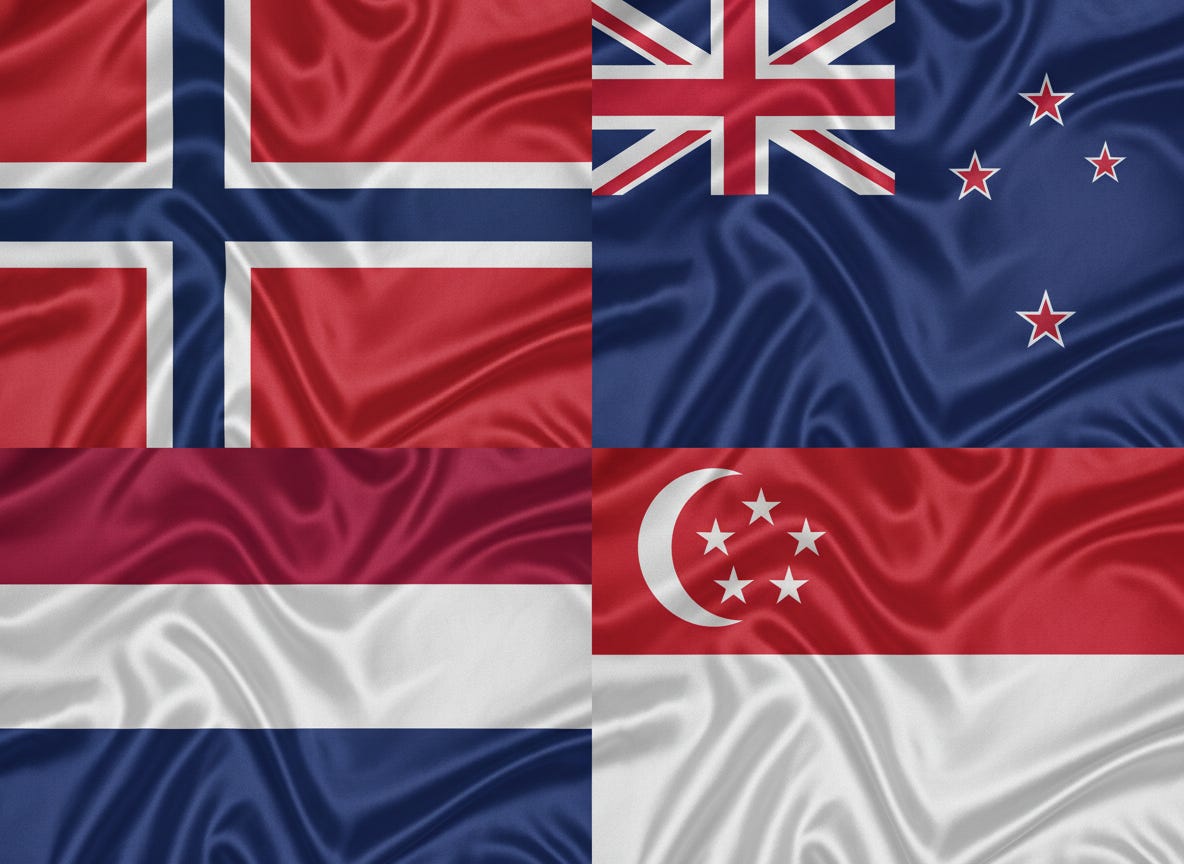

Four government systems the deliver results

There is no best system of government.

A belief that there is a best system is a reaction to the propaganda and ideology we’ve been fed, and a good dose of ignorance.

The idea that one political model represents the endpoint of human progress is comforting. It flatters those who benefit from it. It builds national cohesion and helps keep the elite in pow…