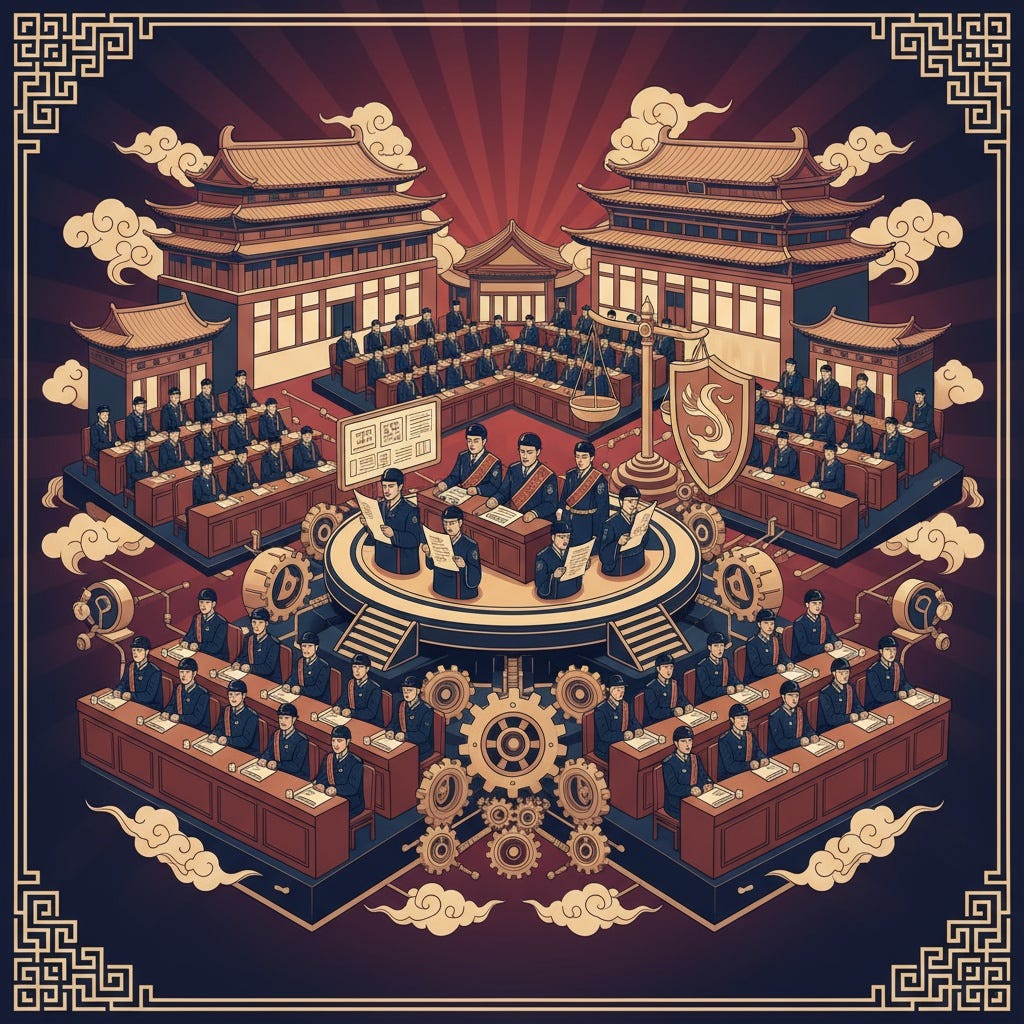

Friday Edition — Execution and Oversight: How China Turns Policy into Action

How the Chinese government really works

This week, we’ve seen how China’s government works from the ground up.

Tuesday explained how leaders are chosen through merit.

Wednesday showed how consultation replaces competition.

Thursday revealed how the Politburo and its Standing Committee set national direction.

Today, we look at what happens next, how decisions are implemented.