Developmental State - The Transformation Model: Friday's Edition

Four government systems the deliver results

Western political theory preaches that democracy comes before prosperity. Establish rights, hold elections, build institutions, and success follows. This sequence feels natural to those from countries that industrialized a century ago.

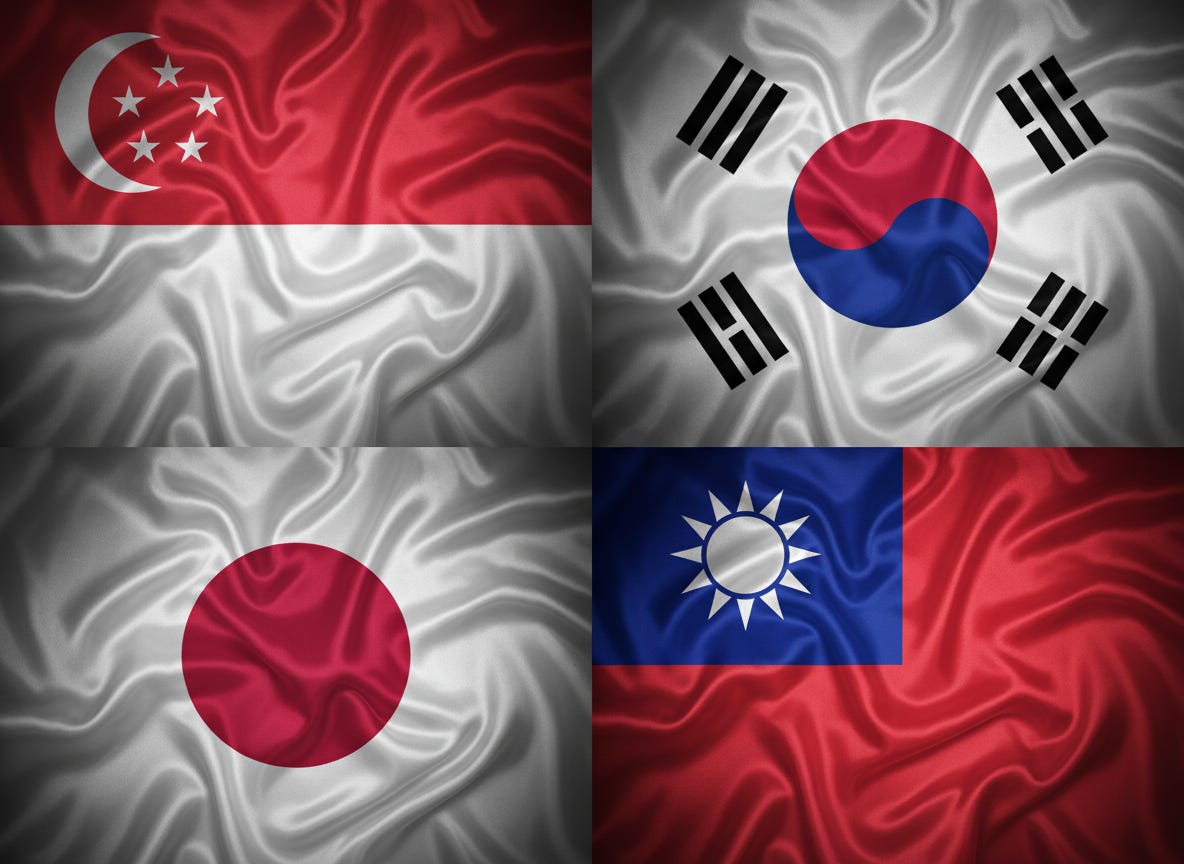

Singapore, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan ignored this script. They grew rich first. Democracy came later.

These countrie…